Documentation is stupid

There are lots of reasons to hate documentation:

- It takes time away from development, and if I wanted to be a writer I would’ve majored in English

- Its accuracy can never be 100%, and the information represents a snapshot from the past (and not the current system) that immediately goes stale upon publishing

- There’s a special circle of Hell (for software who supported SOPA) where all they do all day is review Word documents and merge new versions

- There’s always that one guy on the team who can somehow ignore the fact that there are red squiggles under 10% of his words and CAN’T YOU SEE THAT YOUR SPELLING IS ATROCIOUS, DAN

Lots of hate for documentation.

So why do we still do it? Well, there are certain documents that most projects with more than one person should have (they don’t have to be separate documents) (I love bulleted lists):

- “New Member Guides” – how to set up your environment, acquiring source code

- Various process documents – check-in, review, continuous integration, etc.

- Some kind of Project Charter so everyone knows why you’re building what you’re building

- Some kind of requirements, even if it’s a rough sketch on a napkin

There are other documents that you should consider under other circumstances, like:

- If you’re working in a regulated industry, you’re beholden to some body that likely requires additional documentation or records (design documentation, proof of code reviews, etc.)

- API documentation if you have an interface that will be consumed by anyone ever

- Marketing stuff

- User manuals

The problem?

I don’t mind writing documentation as long as it’s useful in some capacity. The problem for me was the overhead.

When you start talking documentation, especially documentation that needs to go through some kind of review and release process, there’s a lot of stuff that has to happen.

First you write the document, generally in Word, because “reasons”. Then you email it (or post on SharePoint) for someone (or multiple someones) for review. Then you get back at least one document hopefully marked up in a sane way (“I have Word 97 and couldn’t track changes so I printed it out and I couldn’t find a red pen so I used fuschia”) and incorporate the changes. Then, if your lead is pedantic (like me), more review to make sure you didn’t miss anything. Then you version the document and put it on SharePoint, where it slowly becomes irrelevant because nobody reads it, and it’s probably in the wrong folder anyway.

Oh, all of the editing is done in some inscrutable template that was designed for Office 2000 and we keep around for legacy reasons. Good luck using tables! Seriously, you should probably lock up any nearby sharp objects for a while.

MarkDown isn’t stupid

Markdown lowers the amount of overhead.

If you’re not familiar with MarkDown, there’s a little bit of information about it under the rest of the post. Go look! But after you read about the results of using MarkDown on a Real World Project.

Results of using MarkDown on a Real World Project

(Thanks to git_stats for generating me some sweet statistics)

We used MarkDown for documentation on the last major project I was on (started with one team of 8 for about 5 months, increased to 2 teams and 15 people for another 4 months). Here is the breakdown of commits per role:

| Role | Team 1 commit count | Team 2 commit count |

|---|---|---|

| Scrum Master | 71 | 0 |

| Tech Lead | 20 | 27 |

| Developer | 83 | 17 |

| Tester | 4 | 0 |

| Total | 178 | 44 |

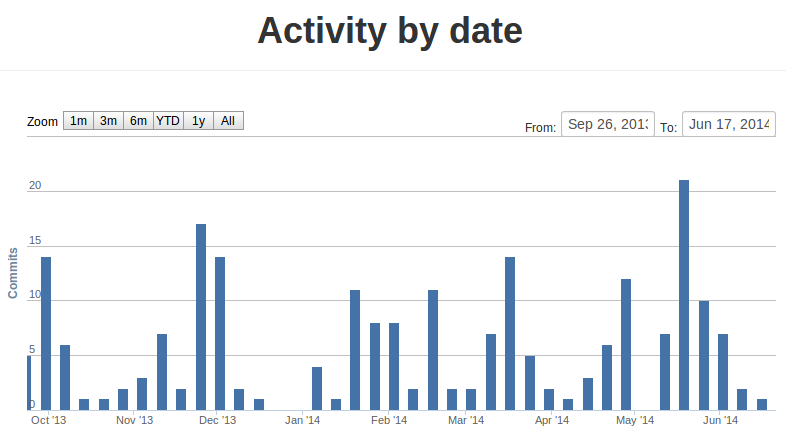

And an activity graph, why not!

Plusses

The documentation seemed to be updated more frequently and remain relevant longer than what I’ve seen on other similarly sized projects. Often when a new team member came onto the project he would feel free to update any bits of documentation that had gone stale and push it through the review process.

With the lowered overhead of updating documentation, it became common to include acceptance criteria for a feature detailing what changes were necessary for which documents.

Minuses

There were a few processes we could’ve put in place to help guide us for the following:

- Versioning documents. As it was, we simply appended a datestamp to most documents as they went out the door. This works in that it is traceable, but feels loose enough that it might not fly in the more regulated industries.

- Sunsetting documents. Once a document became irrelevant it sat in the repository, gathering dust. It probably would’ve been a good idea to outline the criteria for document removal.

- Since it’s all code anyway, we could have easily spent a few hours to write a number of small scripts that would handle versioning and uploading to the wrong folder in SharePoint.

- Or, wouldn’t it be cool to hook the thing up to Jenkins and have it run a spell/grammar checker, version, and generate your artifacts for you automatically? Man, I wish I would’ve thought of that months ago.

One of the biggest reservations of using MarkDown was the inability to use the client’s Word template for certain documents. Again, we probably could’ve written a single script to have the release process copy the text into the template.

Conclusions!

Originally I had a dream of everyone using LaTeX, because LaTeX makes me feel warm and fuzzy. MarkDown was a compromise that seemed to work out pretty well. The first team adopted the approach pretty readily, and there were no mutinies, so I consider the experiment a resounding success.

I’m curious to know impressions, feedback, if you’ve tried this on your project, how it went, etc. Comments are appreciated! And mandatory! If you don’t comment I’m going to stand behind your chair staring at you until you do.

MarkDown information!

What is MarkDown?

MarkDown is a markup syntax that lets you separate your document into a source file (written in MarkDown) and a generated presentation file (which can be HTML, PDF, Word, and probably others).

Suddenly documentation is barely different than code. The source file can be kept in source control alongside your code. Since the markup is terse, it’s not challenging to review it using the same tools already in place for code reviews. And to release the document (or generate an artifact) you simply run the MarkDown through a document converter and do whatever you will with the generated HTML, Word, or PDF file (probably store it in the wrong SharePoint folder) (no, I’m not bitter).

Flavors?

MarkDown has a few ‘flavors’, or slight variations of syntax. Among my favorites are:

- kramdown, a Ruby-specific MarkDown library that is used as the default in Jekyll

- GitHub Flavored Markdown

- PanDoc

The core of each of these projects is very similar to vanilla MarkDown. kramdown adds support for filling the generated HTML with class and id attributes. GFM adds quite a bit to do with code formatting (as you can imagine). Pandoc includes a bit of hefty support for tables.

Tools

“But Mike,” I’m making you say, “what about tools for MarkDown?” Wow. I can make you say anything! “Mike, you’re super-handsome and your freshly laundered scent is beyond reproach!” Writing is awesome.

Editors

Because the text is fairly plain you can use whatever editor you want when editing the MarkDown.

- Sublime has a module for MarkdownEditing

- Emacs has markdown-mode, which should be installed through

package-list-packagesyou heathen - Visual Studio has a Markdown Mode extension that isn’t too shabby

vimhas something… probably? I dunno, I’m not going to google ‘vim’. You do it. You google ‘vim’.

Renderers

There are lots of options here, depending on what flavor you’ve chosen:

- PanDoc can generate Word, HTML, and PDFs. If you’re on Windows, you’ll need to install LaTeX as well (the site recommends MiKTeX), and on Windows both can be installed through Chocolatey

- Doxygen supports MarkDown in comments to some extent

- Want to see what your GitHub MarkDown looks like before you commit it to GitHub? Check out grip. I don’t have this one running on Windows, but I like the way it works on my Ubuntu VM.